With the world’s current population growing and so many diseases coming up due to lifestyle choices and the environment, it is no wonder that there is a shortage of a class of people in the world- donors. Every day accidents and happenings have driven the need to get donor organs that scientists have begundeveloping the most unconventional means to combat the shortage.

The first invention was the stem cell treatments because scientists want to make organs in their labs. The second idea explored was three-dimensional printing of body vessels which is a work in progress. Now, researchers from the Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) are in the proof-of-concept stage of making a heart out of the lowly spinach.

How WPI made it work

The WPI set out to work on their project realizing that it would be difficult to manufacture a whole vasculature system because some of its components, the capillaries, are very narrow (5 to 10mm in diameter). It would also be a challenge to get any invented system to work with a constant blood supply is a challenge to any scientist.

For their experiment, the team wrote in The Biomaterial, the scientists went out and bought spinach from a local market. Lead author Joshua Gershlak commented, “We decided on utilizing spinach because it has vast vein networks similar to those of the human vascular system, but we were not sure that our experiment would work.” Other reasons the researchers gave are the abundance and affordability of the vegetable.

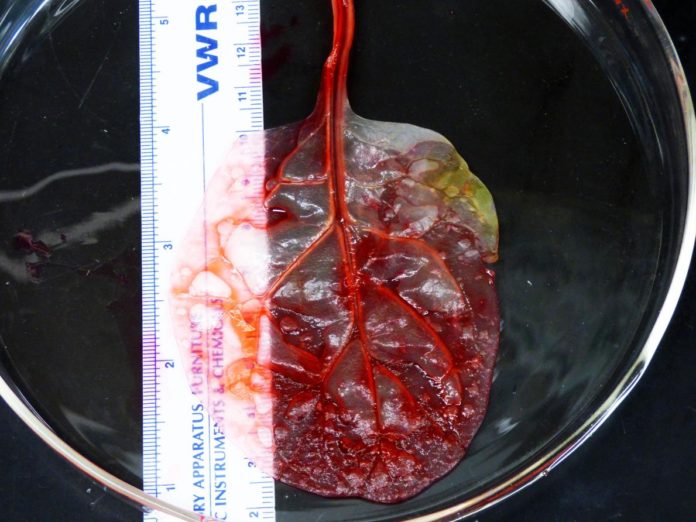

In the first round of their project, the WPI research team stripped the spinach of its green photosynthesizing tissue. What was left behind was the rudimental cellulose tissue that typically binds the leaves of the plant? The scientists found that they could work with the cellulose because it has undergone many studies that have demonstrated its compatibility with human body tissue. Also, cellulose is readily available in plants and relatively easy to grow in a lab.

Gershlak and his team then describe how they ‘decellularised’ the cellulose using a detergent as they would have done a human tissue before seeding it with heart muscle cells. After a few days, the team observed that the heart muscle cells multiplied and spread throughout the cellulose layer. Additionally, the cells made the tissue contract and expand rhythmically like a human heart, and exchanged calcium ions similarly to how they would have been doing in the heart. Glenn Gaudette, who runs WPI, termed the results of Gershlak’s team as ‘promising,’ and indeed they are.

Future Possibilities

Gershlak stated that his team had not tested how to integrate the spinach vasculature into a human heart nor had they layered leaves together to form a complete organ. Nevertheless, their research unlocks numerous possibilities that scientists in future could use to make tissues to replace damaged ones after cardiac arrest or be integrated into the repair of blood vessels in hemorrhagic strokes.

Ultimately this research, along with related ones, accelerates the speed at which scientists are bringing us closer to a future of affordable, green organ sources.