A report published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by the University of Southampton and Historic England has brought to light some chilling practices of medieval man.

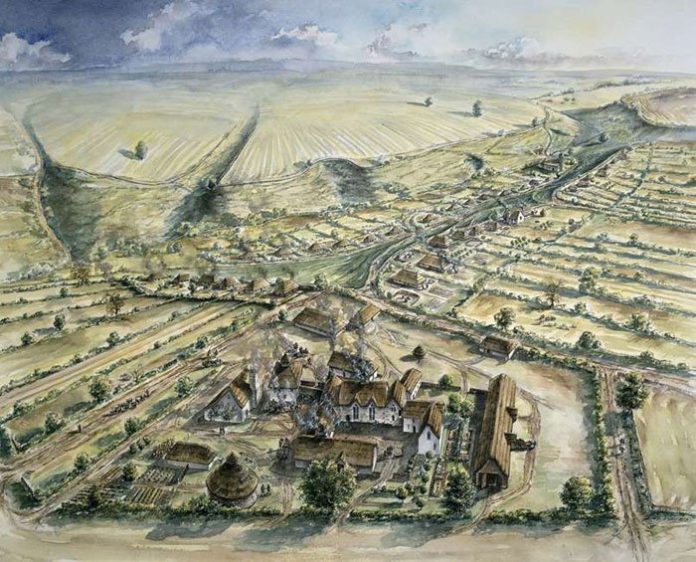

The study conducted by the two institutions was done on human remains discovered in the beautifully preserved medieval town of Wharram Percy, North Yorkshire.

The team of scientists who collaborated on the study examined 137 pieces of bone that were excavated around 1960. The bones belonged to two fully grown females, three children and five men. They had not been examined until this year, and the reason for that was not outlined in the archaeological report.

The bones the team studied had been found under a manor’s foundation in the region, which was unusual as the medieval men typically buried their dead in graveyards or churches. At the time of their discovery, the bones had been thought to be much older than the manor’s foundations but it was later discovered that they dated back to a period the 11th and 14th centuries.

The dating of the bones was only the first shock that the team was to receive.

‘The Bones told a tale.’

Upon close examination of the human remains, the researchers wrote, they unveiled several mutilations to the bone. The bones from the Wharram Percy exaction site had either been smashed or slashed, then they had been burnt.

Simon Mays termed the desecration done to the bones a ‘dark side to medieval beliefs’ which emphasized the different world views help by the modern man and the medieval man. Mays, a skeletal biologist from Historic England, was one of the scientists on the team.

At first, the team thought the damage done to the bones had been sustained during a period of famine. During times when food was scarce, it was not uncommon for the medieval man to practice cannibalism. This assumption made by the team was further bolstered by the fracture lines the team found along longer bones, consistent with bone marrow extraction.

However, the group of UK researchers did away with that hypothesis when it realized that instead of the bones being broken along the joints or muscle attachments, the damaged cluster was limited to the head and neck. It would have been absurdly hard for one man to feed off another by cutting off his head.

Next, the team looked into the possibility that the massacre could have been a result of the North Yorkshire villagers attacking foreigners they perceived as threats. To test out that theory, the group conducting the study took the bones to the labs for isotope analysis which again yielded surprising results. Professor Alistair of the University of Southampton mentioned in a comment, “The Strontium isotope tests help us tell the geology a person was in during the early part of his or her childhood. The results from the bones showed that the remains were for people who lived close to the excavation site, possibly in the village.” So the team discarded yet another theory.

Mays concluded that there was one theory the group agreed fit all the bills. The theory that the medieval man destroyed the remains of those who were thought likely to become revenants or ‘zombies.’ It would explain why the remains were of people who lived in the area as well as why most damages had been done to the head: to prevent the dead from walking out of their graves. The bones told a torrid tale.